A Bullet Removed; A Life Restored

03 June 2022

Karen State, Burma

The Jungle School of Medicine Kawthoolei (JSMK) continues to innovate and improve its services to those living in Karen State, Burma, with the help of international doctors and surgeons who visit and volunteer their time. Often from highly educated backgrounds, these medical professionals’ perspectives not only serve the students, staff, and patients at JSMK, but help get their stories out to the world as well. One surgeon in particular experienced a unique patient case earlier this year. His story is below.

“Thara!” Thara means teacher, and is also a term of respect. “Gunshot wound to the chest last night.”

I responded, “Last night!?” and wondered why the staff hadn’t woken me when he arrived. It turned out that this patient with a gunshot wound to his back had indeed arrived last night, but the event had happened many months before. When I met this man, his aged face revealed how much life he had endured already, though he was not much younger than me.

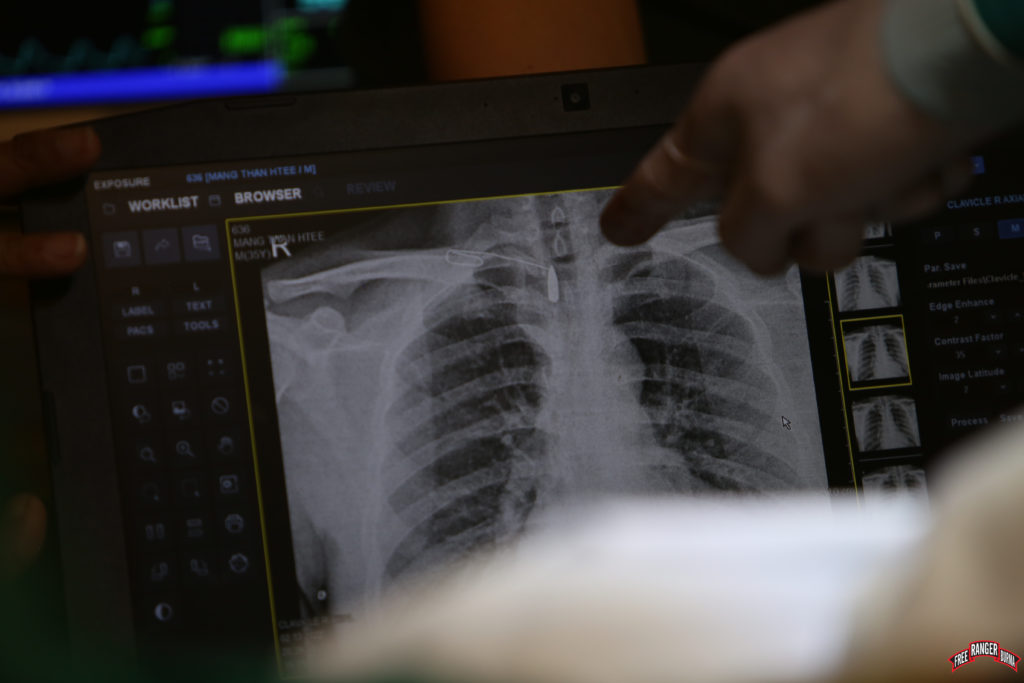

As the patient shared his story, we learned that he had been ambushed by the Burma Army and as he fled, was shot at close range with an assault rifle. I found his story hard to believe. A round fired in such close proximity would have gone through him, leaving him long dead or at least paralyzed. To our surprise when we viewed his xray, we could see a clear bullet lodged in his back. “Should I take it out?” I wondered. I had learned over the years that many war wounds with retained foreign bodies like this actually do not need to come out. As strange as it may seem, thousands of people live a healthy life while carrying bits of metal in them – their only disadvantage being unable to get through airport security without setting an alarm off.

This man’s motivation for coming to JSMK was clearly a personal one. The bullet lodged in his back had been meant to kill him and he felt that it was still a part of him. He said he could not sleep with that thought and had crippling anxiety. In order to remove the bullet, I would have to make a larger incision than the damage the bullet had already caused. The Hippocratic Oath states “first do no harm” and here I would risk causing more harm than good if I could not get the bullet out. The patient weighed his options and decided he wanted the bullet removed anyways.

The next challenge was to accurately find the location of the bullet. The military has a term called “field expediency,” also known in humanitarian jargon as “frugal innovation.” What these terms essentially mean is improvising or re-engineering something for a different purpose. Locating a bullet in a 3D patient with an x-ray that gives you a 2D film is not easy. Using serial xrays and a strong paperclip taped to the patient’s back, I was able to locate the exact position of the bullet. Even during the operation it took much effort to find the bullet, but alas, it was lodged by the facet joints of his spine. That the bullet did not kill him or leave him paralyzed is, again, a miracle to me. The bullet also showed no signs of ricochet as it was still perfectly formed.

An old surgery mentor once told me “don’t treat psychological disease with surgery;” however, deep in the Burmese jungle a bullet had been removed, pathological anxiety had been lifted, peace had been restored, and a young man was able to finally sleep soundly again.

“‘For I know the plans I have for you,” declares the Lord. “Plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.’” Jeremiah 29:11

Thank you and God bless you,

Free Burma Rangers