Yesterday a Doctor, Today an IDP: One Man’s Journey Beyond Rangoon

6 May 2022

Karen State, Burma

Myanmar’s (Burma’s) decades-long history of oppression with cycles of feigned reforms, followed by renewed and violent crackdowns, provides the context for the 1995 film, Beyond Rangoon. The film follows the journey of a foreign physician who accidentally gets swept up in political events, survives, and escapes along hill tribe routes to emerge as one of the few eyewitnesses to the brutality. From a slightly different angle, Beyond Rangoon, essentially dramatizes Dr. Spring’s (name changed for security reasons) story, which is tragic, ongoing, and, sadly, one shared by thousands.

Dr. Spring and his wife are Myanmar nationals of ethnic hill tribe heritage. Unlike most of the country’s hill tribe populations, Dr. Spring experienced the privilege of living in the more peaceful plains of central Burma for many years. He and his wife owned a home, a business, and were raising three children amongst friends and family. Dr. Spring is an internationally certified and experienced doctor, professor of medicine, and published writer who enjoyed his distinguished career while advocating for a freer Burma for over thirty years. His advocacy began when he was a medical student during the 1988 uprising. He describes a turning point later on in his career when he fully rejected his government’s medical system: “In 2007, I resigned from government service [as a doctor] as I no longer believed in the health policy of the Myanmar government. I had come to realize that my service would no longer benefit the people of my country, especially not those in rural areas or the ethic minorities of the hill tribe regions.” Dr. Spring continued working in a private practice while supporting free and fair elections and donating to Internally Displaced People (IDP) throughout his country who were affected by Burmese military violence. Loyal to the cause of Burmese democracy, Dr. Spring never experienced the price of this cause firsthand – until this year.

Three days before February 1, 2021, rumors of an impending coup whispered along the streets of his town. “I didn’t believe this was possible,” Dr. Spring admits. When the military appeared on TV a few days later along with cut internet and communication channels, Dr. Spring knew they had indeed done the “impossible.” His memories from 1988 rushed back. He recalls his feelings in the early hours of February 1: “I had to sit down. I thought deeply about what would happen next. This is not like 1988. Over the last five years we had a test of democracy. [We experienced] what free speech was and freedom for voting, freedom for our human rights. No one had been above the law.”

The coup extinguished any glimmers of hope for democracy that had been dawning throughout Burma. Dr. Spring realized the time had come: it was time to take his years of peaceful protest to the next level by risking his life in civil disobedience. Beginning to grasp the severity the next months would bring, he told his family, “Be prepared, we are going to struggle a lot from this movement.”

Within twenty-four hours of the military’s take-over, Dr. Spring moved from contemplation to action, beginning the coordination of resistance strategies with other professionals in his city. Over the next several months, as the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) took shape, Dr. Spring organized secret medical clinics in opposition to the military’s orders. He and his teams treated thousands of patients, including peaceful protestors who had become victims of the military’s increasingly brutal violence. Out of his own home, using his own money, Dr. Spring gave all he could to support the clinics and those they served.

Retribution for opposition to the coup was implemented early on in February, so Dr. Spring’s clinics had to be mobile and they moved locations often to keep out of sight of the military. Despite months of success, one evening Dr. Spring got word that one of his clinics had been discovered by the junta. While searching the clinic and arresting Dr. Spring’s coworkers and friends, the junta were now en route for him. He remembers it was 6:00p.m. In one hour, the junta would be at his house to detain him and, most likely, his entire family. He had no time to plan; they had to decide what to do immediately. They did the only thing they could: they ran. Barely escaping arrest, and seeing their personal property confiscated, Dr. Spring and his family fled their home on a full-moon night with little more than the clothes on their backs.

Five days after fleeing their home, Dr. Spring and his family secretly watched from a distance as the junta patrolled their home and surrounding areas in search of him. Hiding in their town was not safe enough. He needed to flee much further if he was to be out of danger. “During this time we could not eat or sleep [much] due to fear,” Dr. Spring remembers. It was during this time they were able to make contact with the Free Burma Rangers (FBR). Escorted under the guidance and protection of an ethnic resistance group coordinated by FBR, Dr. Spring and his family traveled beyond roads and armed checkpoints deep into the mountainous jungle. Seven days later, they arrived at FBR’s Jungle School of Medicine (JSMK).

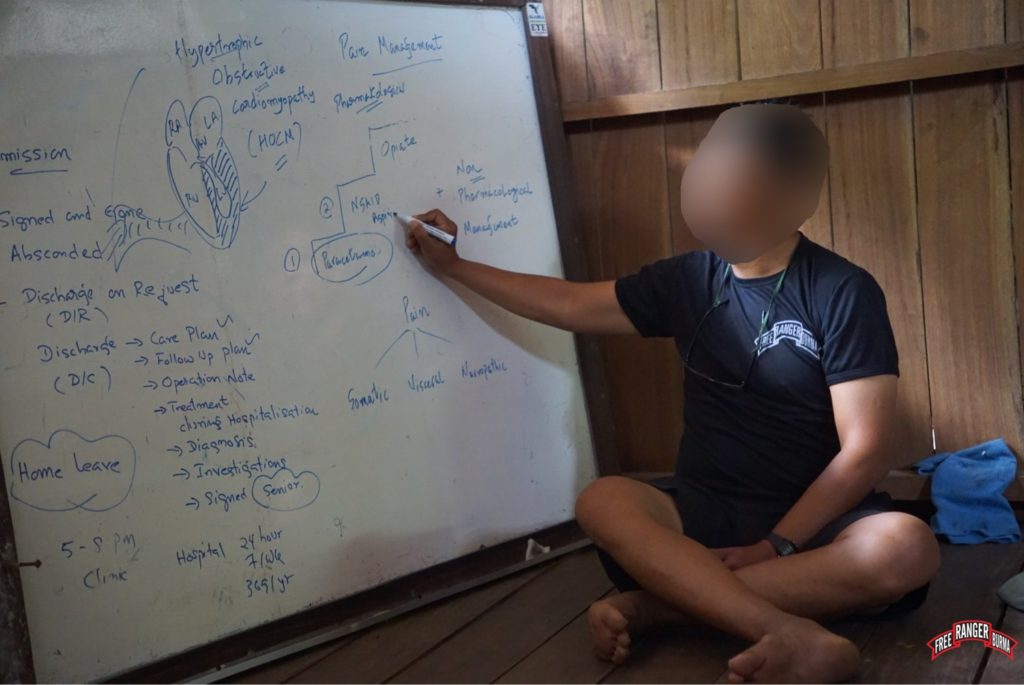

JSMK is a small, remote hospital and medic training facility primarily serving hill tribe patients, some of whom are victims of Burma Army violence. Dr. Spring quickly applied himself at JSMK by treating patients and jumping into the teaching routine for FBR’s medic students. While the war raged on, Dr. Spring also braved the frontlines with FBR where the fighting was most severe. He supported local medics and provided care to casualties there. The increasingly widespread attacks since the coup have drastically affected the needs of those who FBR and JSMK serve and Dr. Spring’s skills and expertise has been of significant value. Yet, perhaps what is most significant is simply what Dr. Spring’s presence at FBR and JSMK represents: for years, those in central Burma, like Dr. Spring, were given a misconstrued reality of Burma through government censorship and propaganda. Many did not understand the degree of oppression their fellow ethnic citizens were suffering under Burmese military rule. A central Burmese doctor now serving alongside hill tribe village medics represents the unity taking place on a larger scale across Burma. In a rare moment, people from all parts of the country are uniting in the fight for freedom for all.

JSMK was originally just going to be one stop on the journey to safety for Dr. Spring and his family; however, as he has spent time working there, they decided to stay to continue helping the revolution. He says, “The coup stands as an insult to the people of Myanmar and as an affront to international efforts at democracy building. As a citizen of the free world I am committed to stand in opposition to tyranny in Myanmar and elsewhere.”

For the foreseeable future, Dr. Spring and his family cannot safely return to their home and continue to live in hiding as political refugees in their own country. They now share the status of IDP with more than one million of their fellow countrymen and women, and yet, there is hope. There is hope because, unlike the 1995 historical drama, Burma’s story is still being written. It is being written by the courageous men and women of Burma, who are laying down their lives each day, like Dr. Spring. Once a doctor donating thousands of dollars to IDPs from afar, he is now a doctor serving amongst thousands of IDPs as one himself; Dr. Spring continues the fight for democracy “beyond Rangoon,” beyond home, and beyond life as he once knew it. “My dream is that one day it [democracy] will happen because it’s not like 1988 … now people are aware of who is the common enemy, Kachin already know about that, Karen already know about that, Shan, Rakhine and even Bamar know who is the common enemy, who makes us poor, who oppresses us. So this is a good time….”

Thanks and God bless you,

Free Burma Rangers